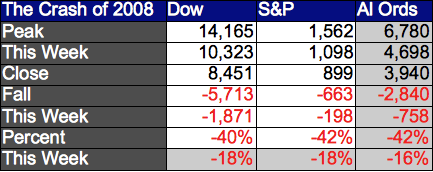

This week, financial markets truly succumbed to The Panic. The US Dow Jones and S&P500 Indices lost 21%; Australia’s All Ordinaries fell 16%. “Buy and Hold” gave way to “Get Out At All Costs”.

When we look back with the eyes of history, the ninth day of the tenth month of 2008 will be the Black Thursday on which the world’s biggest ever speculative bubble finally burst.

The Stock Market Crash of 2008

Friday’s wild gyrations on Wall Street–which saw the Dow down as much as 700 points and up as much as 140, before closing down 128 points for another 1.5% loss on the day–are aftershocks from a financial earthquake driven by tectonic shifts that have a long, long way to go.

The US markets are down 21% for this week alone, and 45% from their peak; the Australian market has fallen 16% this week, and 42% from its peak. The only other stock market crash that compares with this is, of course, 1929.

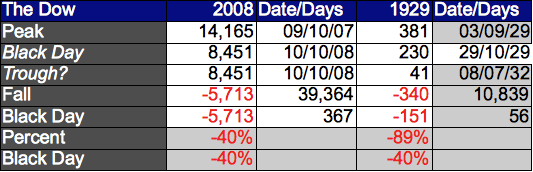

Comparing the Crash of 2008–thus far–to 1929

The fall in 1929 itself was much more sudden–the fall from the market peak of 381 to Black Tuesday’s plunge to 230 points took just over a month, versus over a year this time. But the long grind to the bottom in the 1930s took three years (and the market didn’t revisit its 1929 peak until 1957). We may well face as long a wait before a new world financial order is established.

If we can gain our senses this time, we may be able to establish a financial system that serves capitalism rather than subverts it. We need, as Hyman Minsky argued, a good financial society in which the tendency of markets to indulge in speculative behavior is constrained.

It is obvious now that this will not be a deregulated market. But can it merely be a regulated one? Will regulations alone–bans on short selling, “Chinese Walls” between investment and merchant banking, quantitative regulation of lenders, etc.–be enough?

Clearly they were not this time round. That is the world constructed after the Great Depression (and its political aftermath, the Second World War) when Keynes ruled economics. It fell apart over time because, as Minsky put it, “stability is destabilizing”. A period of economic tranquility ushered in by drastic reductions in debt levels and firm regulation of financial markets leads us to forget the tragedies of The Bust, and to believe that markets are inherently stable.

This delusion was aided and abetted by the economics profession, which reacted to Keynes’s arguments about the inherent instability of markets like an immune system repelling a virus

Economics dreamt up such absurd notions as the “Efficient Markets Hypothesis” (which assumes that markets accurately predict future earnings and value shares on that basis), the Modigliani-Miller Hypothesis (that the most rational funding model for firms is 100% debt if interest payments are tax-deductible), and Rational Expectations (markets are always in long run general equilibrium, and government is impotent to affect real economic activity), and even invented asset market valuation concepts (such as the Black-Scholes Options Pricing Model) that were integral to the development of the derivatives market, the most destabilising force of all in modern capitalism.

Capitalism will survive this crisis, as it survived 1929; and it will be reformed, as was the sober post-WWII system after its profligate predecessor of the Roaring Twenties. But with speculation on assets still a potential path to individual riches–and with a drastically lower level of gearing, as the Great Depression level of debt unwound from its 215% of GDP peak in 1932 to a mere 45% at the start of 1945–the seeds for today’s repeat of the tragedy of speculation were sown.

We need instead to consider redesigning the financial system so that the currently inherent profitability of leveraged speculation on asset prices (when debt levels are low) is constrained.

I propose three such reforms, in full knowledge that they have Buckley’s of being implemented now–but hopefully they will be considered more seriously when this crisis reaches its second or third birthday.

These are:

- To redefine shares so that, as do corporate bonds, they have a defined expiry date at which time the issuing company repurchases them at their issue price;

- To impose “caveat emptor” on mortgage agreements, so that the lender’s security is limited if poor credit evaluations were done of the borrower’s capacity to meet the payment commitments in the contract (this will be further explained below); and

- To base house price valuations on a multiple of the imputed yearly rental of a property, rather than its potential resale price.

The intention of the first redefinition of capital assets (this is much more than a mere reform) is to put some effective ceiling on how high a share price can be expected to go, and to therefore force valuations to be based more on soberly estimated future earnings (of the sort Warren Buffett now does) than on the prospects of selling a share to a Greater Fool–which is the real basis of modern-day valuations.

The intention of the second, which may look paradoxical, is to impose the risk of reckless lending on the lender. Note that a sale of a house by the lender is called a MortgagEE sale–where the suffix indicates that the BUYER is selling the house. The borrower, on the other hand, is known as the MortgagOR–where the suffix indicates that the borrower is the SELLER.

What’s going on? Simple: in a mortgage contract, the lender BUYS a promise by the borrower to provide a stream of payments in the future in return for a sum of money now. The lender is the buyer.

What if the lender didn’t properly check the capacity of the borrower to meet this commitment? If we imposed the old Common Law principle of caveat emptor–“Buyer Beware”–the consequences would fall on the buyer. At the moment, lenders avoid the consequences of poor research into a borrower’s capacity to meet the payments by getting absolute security over the asset the borrower subsequently purchased with the lender’s payment.

Were caveat emptor imposed by the courts, I think that lenders would be rather less willing to indulge in the frenzy of irresponsible lending that has marked the end of this long speculative bubble.

The intention of the third reform is to base lending for house purchases on the income-generating capacity of the asset being bought, rather than as now on the resale price potential. If a multiple of, for example, ten times annual imputed rental income were the basis of valuation, then it would be more than possible for a landlord to borrow money to buy a property, and rent that property out at a profit.

This would establish a firm link between the valuation of a house, its rental income, and the maximum loan one could secure to buy it. It would forge a link between an assets valuation and its income earning potential–a link that is so fragile in today’s speculation driven market. It would also establish a class of wealthy agents–landlords–who have vested interest in keeping house prices and loan levels low.

With such reforms, there is at least some prospect that I will not have a successor writing of the follies of the Stock Market and Housing Market Bubbles of 2060. Without them or similarly effective structural alterations, with merely regulations as were imposed after the Great Depression, we will be here again some time in the future.

All that is, of course, for the future. The immediate problem is what to do now, if, as so many more expect than once did, this market crash is the prelude to the world’s second Great Depression.